Cover 3 is a weekly feature column written by PewterReport.com’s Tampa Bay Buccaneers beat writer Trevor Sikkema published every Tuesday. The column, as its name suggests, comes in three phases: a statistical observation, an in-depth film breakdown, and a “this or that” segment where the writer asks the reader to chose between two options.

SIKKEMA’S *SCHEME* OF THE WEEK

If you were paying attention, you probably noticed the title of this section of the Cover 3 is different this week. If you’d like to know why, allow yourself to recite the tune of Lesley Gore’s “It’s My Party” when reading: It’s my column and I’ll do what I want to. I’m partially kidding, but not entirely.

The idea for this came from a brainstorming session about what to do with this week’s Cover 3. As I pondered over what Bucs fans have been debating on lately, one debate stood out in my mind with no in-depth answer and that is who the Bucs would rather have between Dalvin Cook, Christian McCaffrey and Leonard Fournette if all were available, and even if all weren’t available, what should the team’s big board ranking of those backs be, if they were to take one in the first round?

Florida State RB Dalvin Cook – Photo by: Getty Images

Most of the answers I’ve seen for this question have been production-based. The evidence used in the debates are fans recalling big runs by each and how they happened. But, that’s not the whole story with these three. Though talented, each has a different style and skill sets. So, as a response, I thought about breaking down each of the three back’s styles of play and making a Cover 3 about it.

But, as I began to map out what such an article and breakdown would look like, I couldn’t get far into any of the three without having to explain the type of offensive scheme – more importantly, the offensive line scheme – needed when properly describing how effective each could be on the Buccaneers and as future pros.

So, what I have decided to do is give you not just pieces, but the whole pie – apple pie, preferably. We’ve heard draft experts and NFL personnel members talk about these backs and reference the “system” they need to be in to get the most out of their certain skill sets, but those systems are hardly ever explained when giving such an answer.

This week I’m going to change that. We’re going to start this week by breaking down the three types of offensive line schemes: zone, man and gap. We’ll analyze what each looks like technically, and which run plays fit under each scheme. Then, on the next page, we’ll look at some Buccaneers game tape from 2015 and 2016 to identify which of the three systems the Buccaneers are running with the kind of offensive line they have.

Following our offensive line breakdown this week, I’ll dive deep into Cook, McCaffrey and Fournette next week – and perhaps some other running backs – identifying skill sets, styles and tendencies, seeing which offensive line scheme is ideal for each player, then be able to make a *final* conclusion on where each of these three would rank on the Buccaneers’ big board to determine if any are worth a first round selection when it comes to marrying their running styles with Tampa’s current running scheme.

With all of that in mind, let’s start our X’s and O’s journey where the game begins: the trenches.

Intro to Blocking Schemes

A lot of the terminology and images from these three concepts is courtesy of Rich Alercio, who is an Offensive Line Researcher for X&O Labs. In his article explaining the 101’s of each blocking concept, Alercio identifies that not all running plays have a place in all three blocking concepts – not that they can’t, but they shouldn’t, if you’re looking for consistency.

Like most areas of the game of football, confidence elevates play. If you’re playing confident, chances are you going to get the best out of your own talents and the talents of the players around you. No place on the football field is that more important that in offensive line play. If the unit of five players are all gelling together with confidence, it’s hard for any front seven to neutralize what they’re doing. With that in mind, confusing an offensive line by throwing in multiple blocking schemes and different run plays within each can affect confidence by confusing or disrupting chemistry. To avoid this, it’s much better to establish an identity and build the pieces to best execute that identity instead of trying to do everything. You don’t have to use all three blocking schemes to throw a defense off. It’s better to be elite at one thing than be average-to-good at all three – much like Chipotle proves against their competitors, but I digress. Not that if you’re a good man blocking team that you’ll never run zone or vice versa, but knowing what your offensive line is best at and marrying that with the type of ball carrier you have is what makes the best running teams the most effective ones.

Here’s how each run play can be categorized by the three schemes. I’ve attached links to each play so if you click on them, you’ll see the design. I’ll explain some of these plays in more detail when I get into the three schemes below.

[table id=8 /]The more you watch football under a microscope, the more you’ll realize that a player’s first step is everything. For defensive backs, when and where a first step is taken could be the difference between making a play or not. The same can be said with offensive linemen.

Football is very tedious, and before we dive into what the three blocking schemes are, we have to understand what they ask their offensive linemen to do in terms of footwork. There are five different kinds of steps an offensive lineman can make off the snap. All five are premeditated and usually tell whether or not the play will be a success or a failure.

So, now that we’ve properly identified which run plays can be categorized where and the footwork it will take to pull them off, let’s get into why each run play is categorizes the way it is by breaking down the three main types of blocking schemes.

Zone Blocking Scheme

On paper, a zone blocking scheme is the easiest to perform because it’s all just dependent on where the the run play is going. If the play is going to the right, the entire offensive line’s first step will be a lead step or side step to the right, and they will take the gap and/or assignment that is directly to right right. If it’s to the left, they will first step left and take whichever player is aligned closest to the gap on their left.

The point of this is to get the entire offensive line (and, as a result, the entire defensive front) to move horizontally so the ball carrier can have an easier time running vertically.

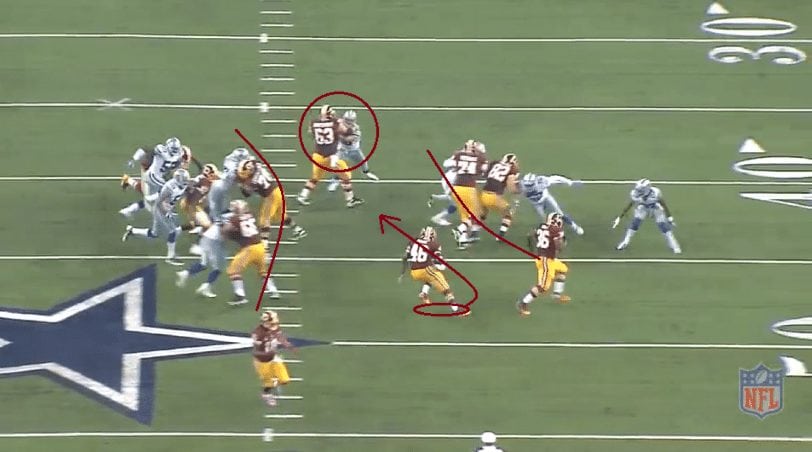

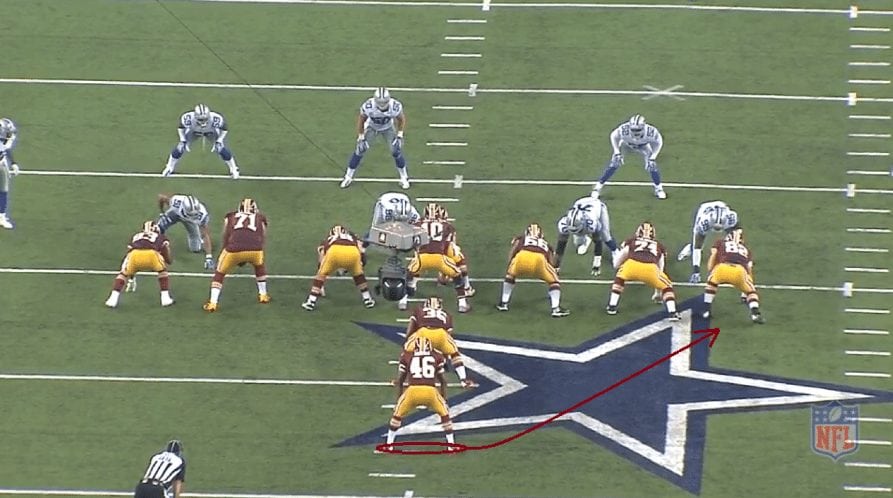

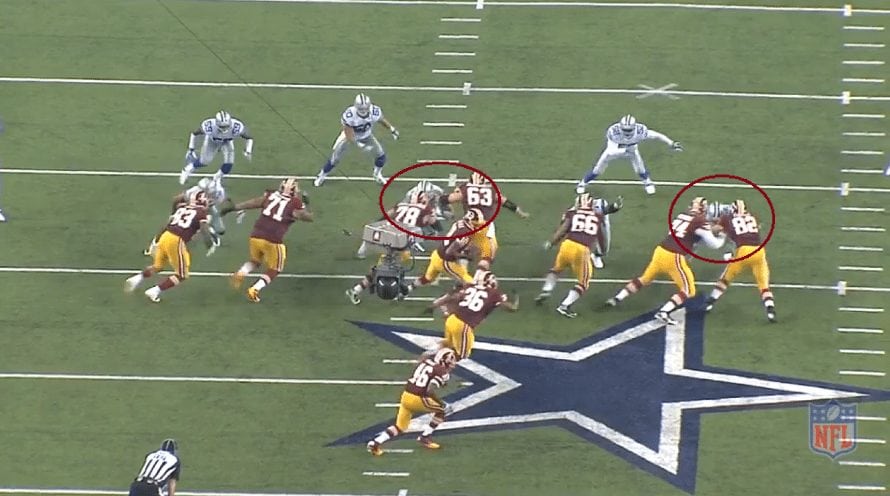

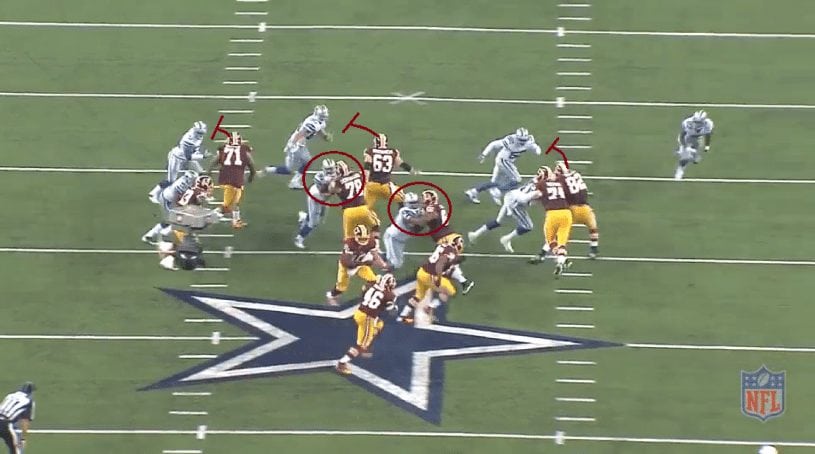

(Images via Washington Post)

One of the differences between zone and power schemes is that in a power scheme there will be a designed hole for the running back to go through (ideally). However, in a ZBS (Zone Blocking Scheme), there isn’t necessarily a designed gap, just a point of attack in either an inside or outside design.

In a ZBS, the offensive linemen will always have their first step to the play side and will take the first assignment they come in contact with on the play side. But, what happens if there isn’t an immediate target to that play side? If that’s the case, the offensive lineman will then go to the second level and seal off the defender (who should be sifting to the play side) on their play side shoulder as to stop him from flowing in the direction of the ball carrier. This is what helps create multiple points of attack for the ball carrier to choose from.

(Images via Washington Post)

In the screen caps above, see how each of the offensive lineman who did not have an assignment on the line of scrimmage to their immediate right went to the second level and positioned themselves to seal off the linebackers from flowing to the play side? That’s what created the eventual running lane.

I used the example of a stretch play above because it emphasized the first step more because it was an outside run. On inside zone blocking run plays, there is still lateral movement in unison along the line, but it is at more of a vertical angle to get into the second level quicker.

To pull off a good zone blocking unit, you have to have offensive linemen who move laterally very well and be sound in their footwork. It takes big players with light feet and good chemistry along the line in all areas to seal off the right defenders. It’s simple in its concept, but when perfected, can neutralize even the best front sevens. The Cowboys are becoming the go-to example of this lately, but its success aren’t new as the Broncos of the 90’s and Houston Texans in the 2000’s made their money off the ZBS as well.

Man Blocking Scheme

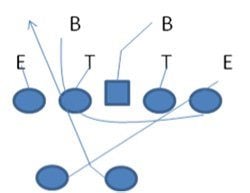

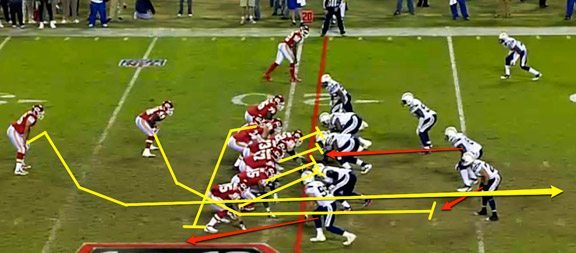

Unlike in a zone scheme, a man scheme assigns certain defenders to each offensive lineman, depending on which side the play is going towards. This changes a few things. First, it’s much more about personal accountability and winning your assignment more than it is about chemistry and flow. Essentially, you know where your man is, go block him. The second is that there is a definite hole or gap the running back is suppose to run through. In simplified terms, a man blocking scheme holds true to it’s “power” family tree because it’s about much less thinking and moving and more about overwhelming your assignment.

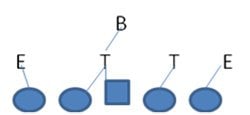

Normally, against a 4-3 look, a man blocking scheme will have the two guards blocking the two defensive tackles and the two offensive tackles blocking the defensive ends, which ideally lets the center get to the second level to take on a linebacker. So the guards are going to be more of those big mauler types more than those quick and agile types. Here’s how that looks against an even (common) front.

But, as you would often guess, defenses don’t usually want to make things that textbook for offensive lines. One variation they have, especially if the defensive line is looking to take up as many gaps as possible, is to put one of the defensive tackles in a nose tackle alignment closer to the center. If this is the case, in Man Blocking Schemes, the center will double-team the nose tackle to start if he is lined up as a 1-tech (outside the center’s shoulder), pushing him towards the guard, then will release to the second level. If the nose tackle is lined up in a 0-tech straight in front of the center, the roles will switch and the guard will be the one to release to the linebackers. Example below.

Here’s how a Man Blocking Scheme looks on an Iso run play.

As you can see, the MBS concept makes sense when running this play. The guards take the defensive tackles, the offensive tackles take the defensive ends, and on Iso plays, the fullback acts as the lead blocker, and his assignment is the play side linebacker at the second level. Here’s how that would look against a 3-4 set up instead of a 4-3.

No unison movement, no shoulders to seal off, just getting into your assignment, knowing where the double-teams should go and physically dominating your man.

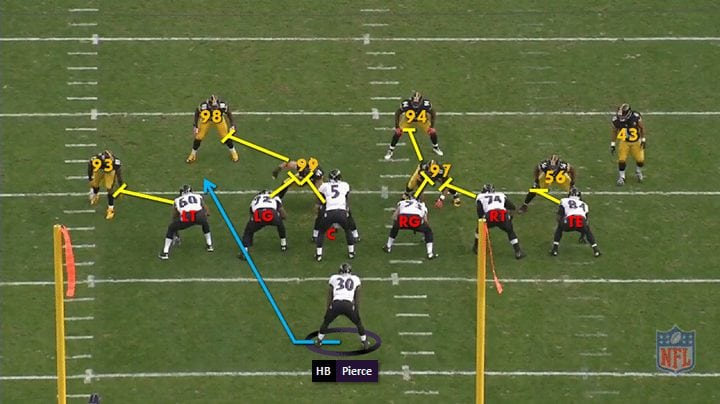

Finally, let’s look at how to run counter in the MBS.

Running counter is a little different, because it does involve a pulling offensive lineman, but it’s still considered an MBS because of how the hole is opened up.

In a counter play, the guards take the defensive tackles, the play side offensive tackle takes the play side defensive end, but the shade side offensive tackle actually swings to the play side and becomes the lead blocker while the full back or tight end then comes behind to engage the shade side defensive end so he doesn’t catch the running back form behind. The point of this is to throw some creativity into a Man Blocking Scheme while keeping its identity.

Gap Blocking Scheme

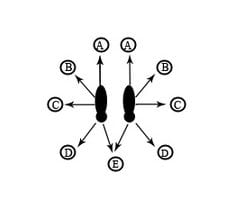

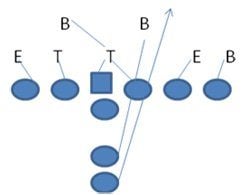

The final tree of blocking schemes is the most complex and that is Gap Schemes. In a Gap Scheme, not only are there moving parts like a ZBS, but there is also movement against the grain like you would see on counter runs in a MBS. Because of the complexity of the scheme, there are only two plays that identify as Gap Scheme plays: Power and Counter Trey.

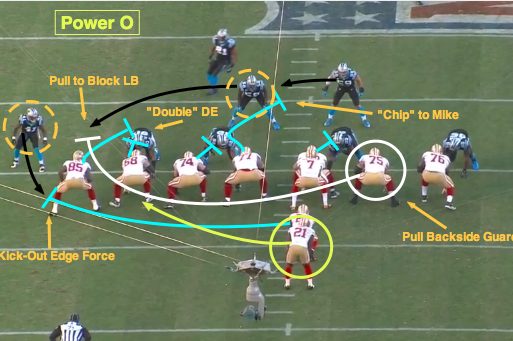

In Power concepts, every offensive linemen, except the back side guard, steps with their back side foot to block their back side gap. The back side guard, on the other hand, pulls to the play side to lead block and take on the first LB on the play side. The play side defensive end on the line of scrimmage is blocked by the fullback, who is the lead back, since the offensive tackle on the play side is stepping to his back side with the rest of the offensive line.

Here’s a visual because I know that was confusing.

(Image via Bleacher Report)

This contrasting movement along the offensive line is designed to open up bigger holes since there is so much counter movement going on. If all goes according to plan, the entire front seven minus the play side defensive end is being blocked to the opposite direction, while the play side defensive end has no help and two lead blockers coming at him.

A Power running play in a Gap Scheme requires an athletic guard and agile offensive linemen. Essentially you really can’t have a weak point on your offensive line. For a running back, their job is relatively easy, they just have to be a little more patient than in a Man Blocking Scheme where every offensive lineman’s first step is forward.

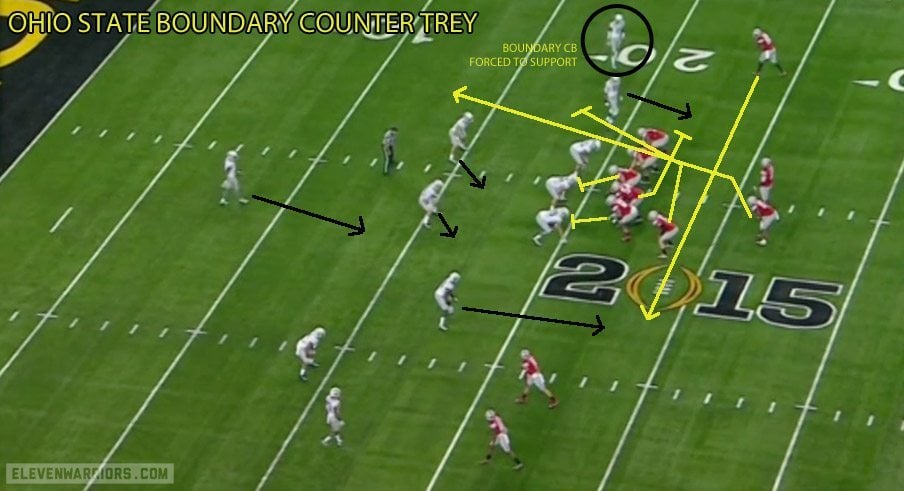

Finally, a well executed Counter Trey is one of the most mesmerizing running plays in all of football. In it, both the back side offensive tackle and guard both flow to the play side of the run, while the remaining offensive linemen move the opposite direction. The pulling back side tackle takes the B gap on the play side and the pulling back side guard takes the outside lane.

Though it’s traditional to pull both the guard and the tackle into the play side gaps, it’s not required. Sometimes, if there is a fullback on the field, a team can run Counter Trey and substitute the back side offensive tackle moving for a fullback.

See how in the play above, the guard and fullback move to the play side, but all the other offensive linemen move the opposite direction? That’s how we know this is still a Gap Scheme play. The man (or assignment) isn’t the emphasis, the gap is.

But, as the game of football has evolved to incorporate much more spread offense and shotgun sets, the Counter Trey plays have had to evolve with it. One of the best examples of how to use Counter Trey from a shotgun or option offense can be seen from Ohio State.

It’s not as common in the NFL since defenders are much stronger and more athletic than they are in college, but that’s what a successful Counter Trey concept would look like from a shotgun set, even without the read option. The guard and tight end (who is in a Wing T set up) both move to the play side on the right while the other offensive linemen block to the left at the second level. This was a big reason why Ezekiel Elliott’s transition to the NFL was so smooth. He went form one of the most complex and effective offensive lines in the country at Ohio State to its NFL equivalent in Dallas.

And thus ends our short (ha!) intro into blocking schemes. How a team chooses to identify itself along the line is arguably the most important part of an offense. Each scheme has its success, but each demands something different from its offensive linemen.

When it comes to the draft, ZBS linemen need to have quick 10-yard splits and above average short shuttle times as to get out of their stance and into their side gaps as quickly as possible. They also need to have good knowledge of the playbook and their teammates’ tendencies around them.

In a MBS, strength, balance and size are key. You have to be physically dominant up front, and need to be able to really push defenders around to open up designed holes.

And in a Gap Scheme, you have to be carful in building a team that has agile players at the guard position and strong players on the outside – sometimes teams will mix and match. These are ideally your prototype offensive linemen. Execution requires both good talent and good coaching, but can prove to be the most successful, if run correctly, due to all its moving part. Ultimately, the type of offensive guards a team drafts will tell you a lot about what they want to do with their offensive line – not that they’re necessarily the “cornerstones”, but their styles usually matter most.

Each scheme asks certain characteristics of the offensive linemen that block in them, but it also asks certain skill sets of the ball carriers who follow their lead. Next week we’ll take a look at the draft’s big three, Cook, McCaffrey and Fournette and identify which back would thrive in which blocking scheme.