Sikkema’s Stat of the Week

I believe the game of football is so popular because it can relate to those who choose to enjoy it on any level of its complexity. If you just like observing casually, appreciating when a dynamic, long play happens that results in points, you can do so and not get much below the surface at to why it happened the way it did and instead just enjoy it for what you just witnessed. But, on the other hand, there are levels of cause and effect that can go just about as deep as you want, all the way to intangible levels, for why plays, points and results come about the way they do in football.

At whatever level you choose to enjoy or understand, it’s fair to know that when you can keep things as simple as you can while still having success, you do that. That’s why the old phrase “it’s all about what happens in the trenches” is true. When you win in areas that are closest to the football, you’re probably going to be successful. This is also why the staple of the game comes from running the football.

Think about it, even in an age where passing is more central to point-scoring in 2018, there are so many moving parts in a successful pass play. There has to be good blocking for an extended period of time, which involves chemistry and talent. There there has to be the correct play call combined with the correct talent. The ball has to be released in the air, making it completely unguarded, and it has to be timed correctly to get it to a fellow offensive player with no bumps in the road. There’s a lot that goes into that.

You know what goes into running the football? Handing the ball to someone and him running with it.

This is why the run game was such an emphasis when football was in its infancy. The best players were trained to be running backs, and the players that had size, strength and athleticism were trained to be the offensive linemen. They could control the game because they had so much, well, control over what happened with the ball. They could keep it simple and still score enough points to win. But that’s no longer the case.

Since 2010, the league has averaged more than 22 points per team per game in each regular season. Before that, to find a single season in which the league averaged over 22 points per team per game you’d have to go all the way back to 1965. Since 2010, the league has averaged 0.77 rushing touchdowns per team per game. Before 2010, there were only four seasons, 2007, 2001, 1997 and 1992, in which the league averaged less than that going all the way back to 1938. In fact, between 1938 and 2010, most of the seasons recorded had teams finishing with an average above one rushing touchdown per team per game, which comes out to about four more rushing touchdowns per team per season. The points total is up but the rushing totals are down. Why? Because when a team emphasizes running the football over honing its passing attack as the emphasis and making the running game instead more of a compliment, it can’t keep up.

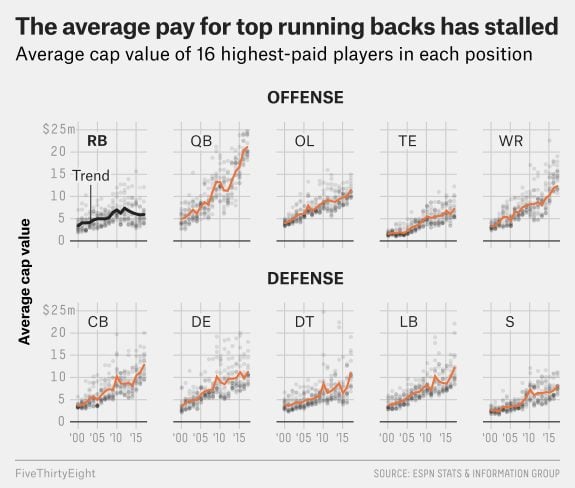

Contract numbers reflect this, too – remember, you can tell what a team really believes in by where it puts its money. People can lie, smokescreen, and say whatever they want, but when it comes to putting money on the line, those with money don’t like putting it in places they don’t think they will get a positive return on investment. This chart from FiveThirtyEight explains that, as the salary cap has gone up, and thus the numbers for most positional contracts with it, running back contracts have actually gone down.

As you can see, almost every other position up to the year 2015 had increased pay in terms of amount overall except for running backs. Since then, the safety position has also declined, but even those contracts aren’t as much of a widespread downgrade like it has been for running backs.

So what gives? Running the ball still matters. I mean, there’s a reason why almost every team in the NFL hands the ball off on their first play of the game. It’s simple, and if it works, why go away from it? There’s no way it just stopped working. Well, no, it didn’t stop working, per se, but its efficiency has shifted as the game has evolved into more of a passing league. Two stats that tell us that are: marginal efficiency and marginal explosiveness.

Marginal Efficiency: the difference between a player’s success rate* (passing, rushing, or receiving) or success rate allowed (for an individual defender) and the expected success rate of each play based on down, distance, and yard line.

Marginal Explosiveness: the difference between a player’s IsoPPP** (passing, rushing, or receiving) or IsoPPP allowed (for an individual defender) and the expected IsoPPP value of each play based on down, distance, and yard line.

For offensive players, the larger the positive value, the better.

* Success rate: a common Football Outsiders tool used to measure efficiency by determining whether every play of a given game was successful or not. The terms of success in college football: 50 percent of necessary yardage on first down, 70 percent on second down, and 100 percent on third and fourth down.

** IsoPPP: the average equivalent point value of successful plays only.

Bill Connelly of SB Nation does a lot of really great work with numbers and advanced analytics to try to bring context into decision making. Before the draft this year, Bill used the marginal efficiency and marginal explosiveness databases to explain why it’s not really logical to take a running back high in the draft.

The reason: not many that are chose high make that much of a difference compared to those drafted later.

Between 2009-17, 176 tailbacks rushed at least 200 times in a season, about 19.6 per year. Of that group, 146 of them (83 percent) posted a marginal efficiency between plus-1 percent and minus-10 percent. That’s a pretty significant difference — the difference between a 2009 Jamaal Charles (plus-0.9 percent) and a 2009 Brandon Jacobs (plus-9.6 percent).

It’s also, however, the difference of basically one extra successful carry for every 10 or 11 opportunities, at most about two extra successful rushes per game. Doesn’t sound like such a monstrous difference when you put it that way.

Among the 90 halfbacks who a) were drafted between 2010-17 and b) have been given at least 100 pro carries thus far, few have truly stood out.

Alvin Kamara, your 2017 NFL Offensive Rookie of the Year, is the only back to have produced a higher than plus-3 percent marginal efficiency rate, and only two others have been above even plus-1 percent: Montee Ball and Mike Gillislee. Those three were drafted in the third, second, and fifth rounds, respectively.

Of those draftees with at least 500 career carries, only two players have produced an even slightly positive marginal efficiency rate: DeMarco Murray (plus-0.8 percent) and Ezekiel Elliott (plus-0.3).

But it’s not all gloom and doom for running backs. Their place in the game isn’t going away, and I’m not even so far convinced as to say their “importance” is going away. It’s just that their usage is changing and in their new usage role they’re proving to be more effective than they’ve ever been.

In 2017, of the 25 running backs who averaged 4.0 yards per carry or more, 15 of them recorded less than 200 carries. On top of that, four pairs of those 25 rushers with 4.0 yards per carry or better averages were teammates.

Do you want good players as running backs: yes, that’s an obvious answer. The question is: at what cost? If you’re drafting a running back high, there’s a hybrid way of thinking where a return on investment and something like a wins above replacement idea doesn’t favor the value of a high draft pick, or even having a feature running back, honestly. What is becoming much more common and much more effective, with the right pairing, is having a running back game plan where two or three backs can rotate in situationally. This allows the offense to remain optimally efficient when running the ball as a compliment to the passing game — since it’s already been established that every offense in today’s NFL should be base around the passing game.

Last season, Peyton Barber was the Bucs’ most efficient running back at just under 4.0 yards per carry. Barber had a very healthy average all year long, and the majority of that came from 10-15 carries per game. I think the Bucs would be wise for that trend to continue, even if he is the best returning option. The reason I think they not only should but can continue that trend is because of a man who was drafted (at an appropriate time in the draft) by Tampa Bay who can not only complement Barber but be that ultimate compliment to the passing game, as well.

Read about that and more on the next page.

All-Twenty Tuesday: Bucs RB Ronald Jones

Coach Boone:

Petey how many feet are in a mile? How many?Petey Jones:

I dunno.Coach Boone:

5,280! And you will take this ball and run every single one of them! Your killing me, Petey! Your killing me!

The quote above is from the movie Remember the Titans. It’s a scene during the middle parts of the movie where the team is still trying to find just who their star players are going to be. In it, the running back, Petey Jones, played by Donald Faison, fumbled the ball during a drill and the result was the quotes you read above.

Taking care of the football is a principle that is as old as the game. Any of us who have played the game of football (or even if you haven’t) have surely heard a coach tell them, “Now, I know you didn’t just fumble my football.” It’s important. The ball is the lifeblood of everything. Without the ball, there are no points, there are no wins and there is no success. Every possession is to be treated as a prized possession. That’s why, when you’re the running back and you are handed the ball, carrying the ball should mean something. You have to guard it, protect it, take pride in it.

Bucs RB Ronald Jones II – Photo by: Getty Images

The Bucs’ new running back, Ronald Jones II, knows how important that ball is, but that ball isn’t the only thing he carries every time he steps out on that football field.

Ronald Jones Sr. and his son, who many call “RoJo” for short, bonded over the game of football. They were both drawn to players like LaDanian Tomlinson, Robert Griffin III, Thomas Jones and Julius Jones (having the same last name as those last two probably helped their attention). Jones Sr. took his son to his first NFL game when RoJo was just 10 years old. Jones said it was a game between the Cowboys and Redskins. RoJo was born in Fort Stewart, Georgia, as his father’s profession was that of an Army sergeant, but he spent a good amount of his years growing up in McKinney, Texas. When attending his first NFL game, his dad even got the two field passes for after the game. According to a story by David Ubben, the shy 10-year-old RoJo spent most of the time hiding behind his dad instead of running out onto the field.

In 2008, Jones’ parents divorced and Jones II moved with his mother to McKinney. RoJo and his father kept up regularly after his parent’s split. And just as they were close and open in their relationship as father and son, Jones Sr. was open about the health issues that he had and the results they might bring. Jones Sr. was working at Camp Mabry in Austin, Texas after the divorce as a logistics specialist, and for more than a year he was on the list for a heart transplant.

It never came, and in 2012, just two years after he was able to take his son to his first football game, Jones Sr. suffered a heart attack that proved to be fatal.

Per Ubben, the then 15-year-old Jones II wrote a eulogy for his father to read at his funeral, but when the day came to read it, he couldn’t bring himself to do it; it was too emotional for him. Jones brought that emotion to the football field where he received scholarships to play running back at almost every major school around the country. Though the original plan was to stay close to home (Texas), when Jones visited USC, he knew that was the place for him. But, according to his mother, that didn’t come without its doubts. During his first year there, Jones became homesick and wanted to come back to Texas and play at TCU. But his mother convinced him to stay; so he did.

Away from home, Jones learned to live on his own. He learned how to become a man on his own, on and off the football field. He became USC’s starting running back, joined LenDale White as the only true freshmen to ever lead USC in rushing, and a year later after a fourth quarter touchdown, which helped the Trojans’ seal their Rose Bowl comeback in 2016, pointed to the sky to honor his father, no longer as the child hiding behind his dad’s legs on the sidelines, but rather, the man on the field with all eyes watching.

When Ronald Jones II steps out onto the football field, he isn’t just carrying a football. He’s also carrying a name, the name that he shares with his father; a name that is not only how he’s identified on the back of his jersey, but also who he is underneath it.

With that background now fresh in our minds, let’s break open some film and see what it looks like when Jones, in fact, carries the ball to find out just what kind of back the Bucs are getting.

Most of us know the obvious with Jones. He’s a 5-foot-11, 205-pound, 4.44-running back who gives people flashbacks to Jamaal Charles when they watch him run. He’s a back who can truly be a “home run hitter” and has a chance to take a ball to the house no matter how far he is from the goal line on any given play. But, speed players like Jones often get a “needs to be more physical” label to them, and I chose the clip above as the first example of what I like about him because it breaks that narrative real quick.

RoJo is in no way just a scat back. He’s not a “speed only” player. In fact, two of Jones’ most influential traits within his game are his ability to turn momentum into power and then pairing that with good balance, often fighting for extra yards and never wanting to go down or get off his feet, even after he has crossed into the end zone.

The post above is another example of both of those traits.

Running backs that weigh 205 pounds aren’t typically seen as goal line backs, but Jones’ traits allow him to be. In the play above, he got hit immediately in the backfield, but rather than just give up on contact, Jones not only fought through it, but fought through it at an angle that gave him a chance to break free and then continue to make a better play. He did just that, and even as you saw him get into the end zone, you noticed that he never wanted to go down. He stayed up on his feet. I bet that’s something an old coach of his told him and he’s never let it out of his mind. When you’re a running back, having the mindset to never let anyone take you to the ground is one that comes in handing when accumulating yards after contact (a very needed trait in the National Football League, no matter what type of running back you are).

Though we’ve shown that Jones is more than just a speed back and certainly carries both power and balance in his game, there’s no doubt that his bread and butter is his one-cut ability and his burst beyond that to finish big plays.

In the play above, Jones was once again faced with a free defender coming right at him in the back field. As Jones secured the ball, he was able to completely side-step the defender, but even better than that, was able to put his foot in the ground immediately after and start his charge up field. That ability to quickly change from lateral movement to straight line movement is not a given, even with faster running backs. It’s a rare trait, and Jones’ true “trump card,” if you will, that he carries over other backs of his size and skill.

The play above is another one of many example of Jones’ dangerous ability to relocate and then burst up the field.

That little move from juke to top speed is rare, folks. There is such an explosiveness to Jones’ game. Not only does that kind of athletic ability help him generate power to run through defenders, but it also obviously helps move by and run by them, as well. The play above is seriously one of the cleanest jukes I’ve ever seen, and as he often does, Jones finished his move in style with six points.

When going into the NFL Draft, readers love to hear who a certain prospect reminds them of. Jones often gets the Jamaal Charles comparison. I get it. Both of them wear No. 25, both have those shorter dreadlocks, both use speed as the main component of their game. But I didn’t love the comparison.

I don’t really like doing comps for players very much because, though some have similar skills, many readers take things out of context when comps are mentioned and miss the point, which actually then hurts your case and hard work when scouting a player just because you tried to force a comp. A Bucs fan whom I follow, Ken Grant, actually gave the best comparison for Jones that I had heard throughout the draft season.

“RoJo is more like Chris Johnson for me,” Grant said. “Slasher that runs with some power, and can take any cut to the house if it blows open.”

I love it. It’s so spot on. The clip above is such a good example of that, too. When Johnson was at his best in the NFL, it looked like that play. It starts with speed, turns into open field ability, then a little power and balance to get the extra yards and get where he needed to go.

Jones isn’t just a speed guy, but I wouldn’t call him a power guy either. He’s not strictly a north-to-south runner, but he’s not a dancer in the backfield. He’s not strictly a one-cut guy, but he’s not totally just straight line speed; he has some of both. He’s a slasher; he’s Chris Johnson. It’s a perfect description.

Above is a clip of Johnson at the goal line when he was with Tennessee that nearly mirrors Jones’ play from the goal line earlier.

And here’s an example of Johnson breaking tackles, first through the line of scrimmage, then taking it to the house like the clip of Jones doing it against Arizona State.

And finally, in the clip above, we saw Johnson from a shotgun formation in a zone blocking concept, watched him put his foot in the ground to one-cut up field, bounced off a tackler, put his foot in the ground and get right back up to top speed down the sideline. Johnson had the skills to get it done, but what I loved most about him when I watched him growing up is how confident of a runner he was.

That’s Ronald Jones.

Now, Jones doesn’t have the top-end speed Johnson did, but it’s close, and the style is definitely there; Jones’ highlight reel looks very similar to that of Johnson’s. At their best, both win very similarly. As mentioned a bit there, Jones appears to get more out of his skills and his vision when running from zone blocking formation, but that’s not all he can have success with. We’ll likely get deeper into how much zone versus power blocking schemes we can expect from the Buccaneers offensive line this year in a later Cover 3. Jones is also a willing blocker. He’ll sacrifice some of his advantage with smaller size, but when it comes to pass blocking and pass catching, two needed traits to play on third downs in the NFL, Jones is adequate at both. He needs work with both, but he’s adequate.

When RoJo wants to feel close to his late father Ronald Jones Sr., Ubben wrote that Jones II will put his father’s dog tags around his neck. When he puts those on, he’s reminded that he’s not just playing for his own name, but his father’s, as well – one that they share. In the eulogy Jones II wrote for his father, RoJo shared the power and responsibility he believes he carries along with that ball.

“You always gave me the confidence that I could do anything if I put my mind to it,” Jones II wrote. “Trust me. I will do my duty. Just give me the strength.”

Every time you watch Jones “wow” you with another run, you see his talent, you see that confidence, you see the ball and you see his father.

Now you’ll get to see all of that in Tampa Bay as he is one of the newest Buccaneers.

Read-Option: Feature or Committee?

So what do you think of the Bucs’ shiny new offensive weapon?

Do you believe in the power of a running back committee, or do you think that’s just a result of teams not wanting to pay running backs and it would be better to have a feature one anyways?

And what about the Bucs’ current running back depth. Are you happy with it?

How do you view Ronald Jones? Do you think he’s just a committee guy, or do you think he’s the kind of running back who can really lead a backfield and maybe do so on his own?

Do you buy into the Chris Johnson comparison? If not, who does RoJo remind you of?

There’s plenty to talk about with how Tampa Bay should use its running backs going forward with Doug Martin now gone. Let’s hear what you’re hoping they do.

Who do you want as the starting running back for the Buccaneers on Week 1?

Trevor Sikkema is the Tampa Bay Buccaneers beat reporter and NFL Draft analyst for PewterReport.com. Sikkema, an alumnus of the University of Florida, has covered both college and professional football for much of his career. As a native of the Sunshine State, when he's not buried in social media, Sikkema can be found out and active, attempting to be the best athlete he never was. Sikkema can be reached at: [email protected]