Cover 3 is a weekly feature column written by PewterReport.com’s Tampa Bay Buccaneers beat writer Trevor Sikkema published every Tuesday. The column, as its name suggests, comes in three phases: a statistical observation, an in-depth film breakdown, and a “this or that” segment where the writer asks the reader to chose between two options.

SIKKEMA’S STAT OF THE WEEK

What makes a good pass rusher?

Is it genetics being a quick-twitch guy? Maybe it’s good coaching. Perhaps it’s a royal line of collegiate and professional athletes in the family. Is the main component athletic ability? Where does football IQ come in to play, or does it at all?

What do James Harrison and Terrell Suggs have in common with Michael Strahan and former Bucs legend Simeon Rice? What similarities are there between Von Miller and J.J. Watt? How could the successes of No.1 overall pick Jadeveon Clowney also been seen in undrafted free agent Cameron Wake before he slipped through the cracks?

Bucs DE Robert Ayers, Jr. – Photo by: Cliff Welch/PR

Where’s the common denominator? What trait exists in every good pass rusher?

Believe it or not, there are two traits that can help identify whether or not a pass rusher has what it takes to produce in the national football league. Those two traits are: movement and mentality. Both have to be present; both, in some capacity, lie within every elite pass rusher over the last decade.

If the Tampa Bay Buccaneers are serious about upgrading their pass rushers – a process they begun with the signing of Robert Ayers and the drafting of Noah Spence last year – they’re most likely going to do so in the first round. But there are plenty of first-round pass rushers who are failures. Tampa Bay has had its share in Eric Curry and Gaines Adams. The question is: Is there something tangible within the truth of required movement and mentality that can be measured?

The answer is yes.

Movement: Identifying A Force Player

No matter how smart a players is or how sharp of instincts a prospect may have, if they do not meet an athletic threshold, they simply will not be able to keep up in the NFL.

Such a threshold is identified as the bottom line, the lowest score of athletic ability a player must achieve in order to be effective. Players who exceed the threshold by a greater margin obviously have a better chance of churning out consistent production at the professional level.

The best measure we have towards establishing such a threshold is a numbers-based formula for pass rushers developed by Justis Mosqueda called “Force Players”.

Movement matters, and the way the Force Players formula quantifies that is by using NFL Scouting Combine numbers. The formula (which isn’t public) uses importance percentages from different Combine drill results which altogether places EDGE rushers (meaning 4-3 defensive ends or 3-4 outside linebackers) into three different categories: Force Players (best), Mid-Tier (potential to be quality pass rushers) and Non-Force Players (players that tested limited athletically).

As Mosqueda explains, the formula isn’t perfect – even the most advanced statistical analytics have their flaws or “can’t explain” exceptions – but the “hit rate” for the formula is quite high.

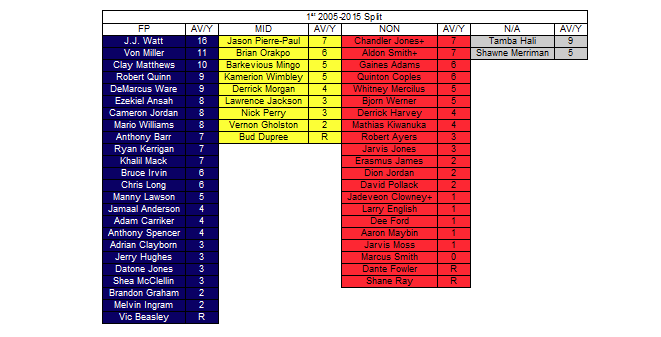

Here’s a look at the Force Player results for pass rushers who have been drafted in the first round from 2005 to 2015.

So the glaring misses on the list of non-Force Players are Jadeveon Clowney, Aldon Smith and Chandler Jones. However, all three of them had either lingering or recent injuries during the time of their testing, and most likely did not test at 100 percent health in each area.

The formula seems to slightly favor 3-4 outside linebackers because they are more athletic in nature than 4-3 defensive ends. However, the Bucs won’t be drafting a pure 3-4 outside linebacker. Let’s see what some of the top 4-3 defensive end Force Players’ numbers charts looks like from a visual aspect using Mockdraftable.com Combine charts.

The three Force Players we’re going to look at are Detroit’s Ezekiel Ansah, Los Angeles’ Robert Quinn and Buffalo’s Mario Williams since those are the type of players who would translate to a player used in the Bucs’ scheme.

The spider graphs can help visualize how well a player fills out a certain area to determine some sort of commonality, but be careful, sometime the graphs are not fully filled out due to a prospect partially participating at the Combine. But the reason I chose these players is because they have participated in the areas we think matter most.

What stands out right away should be how each of these three prospects scored in at least the 50th percentile in the 10-yard split, vertical jump, broad jump, 3-cone drill and 20-yard shuffle. Fans have a tendency to get caught up in 40-yard dash times as the be-all, end-all for athletic ability. This should not be the case, and, really, the 40-yard dash is one of the least telling drills when it comes to NFL success of pass rushers.

Instead, we can break the drills up into athletic categories. Vertical and board jumps measure how much power can be generated from a player’s lower body. A 10-yard split can measure how effective a pass rusher is in using that lower body power (explosiveness) to get out of his stance and around the edge. 3-cone and 20-yard shuffles can help measure ankle flexion, and how much bend a pass rusher can have when turning the corner.

All of these athletic numbers can help measure translatable skills, aspects of pass rushing that are all necessary to get by NFL offensive lineman off the edge.

Let’s look at three high-profile non-Force Players to see if that theory lines of with where we guess Mosqueda’s formula at least begins.

The three prospects we’ll use here are Jacksonville’s Dante Fowler Jr., Miami’s Dion Jordan and Houston’s Jadeveon Clowney, whose failed Force Player numbers should be parallel with what is missing form the rest of the group.

Fowler’s graph, as a whole, is much less filled than the rest of the NFL’s averages when compared to other prospects.

What we notice from his test is that his explosiveness out of his stance from both his 10-yard split and his overall 40-yard dash were off the charts. However, that explosiveness did not translate in either the vertical or broad drills, which should have drawn a red flag. This revealed that Fowler is most likely linear in his explosiveness, meaning he has it in a very specific instance, but not overall with total athleticism. That means he wouldn’t be elite at burst or jump off the snap in every situation, but rather, limited situations.

Jordan’s chart was along the same narrative as Fowler, but he only fails at the vertical jump (his broad jump was even in the 87th percentile).

That goes to show you how important each category is. Jordan likely only failed one aspect of the formula, and due to how it affects the other variables, it failed him as Force Player entirely. This lets us know that there are no cutting corners when it comes to hitting on pass rushers in the first round.

Finally, we look at Clowney.

Clowney recorded elite explosiveness in drills that tested him getting out of his stance, and in his movements overall with high scores in the vertical and board jump. However, due to the bone spur issues that eventually sidelined him and required surgery, Clowney failed to register good numbers turning corners. This tells us that even with off-the-charts athletic ability, ankle flexion and the ability to turn corners matters. Pass rushers must be able to bend edges at almost impossible angles to become double-digit sack players.

This is the best way I’ve found to measure movement for pass rushers. Mosqueda updates his Force Player formula every year to constantly increase its hit percentage, but even now it’s pretty high. There are a handful of instances where drills at the Combine just do not matter for a position. Pass rushing really requires it all.

If a prospect has it all, there only one more characteristic that is needed for success.

Mentality: Crazy Train

There’s no way to truly measure it.

The only way of identifying the mentality of a prospect is to do your research by getting to know a player personally, and doing some background checking from people who know what a prospect is like in and out of the locker room.

Bucs DE Simeon Rice – Photo by: Getty Images

Simply put, the best pass rushers all have a least a hint of crazy in them. Whether it’s Jared Allen’s history of bar fights, Harrison flying home after a playoff game to get a work out in, Rice’s egotistical motivation to be “the man” at all times, or Watt’s insanely detailed diet and lifestyle where every second and calorie is calculated, there’s usually something about all great pass rushers that when you get to know them or learn what they’re really like, you can’t help but laugh and say to yourself, “That dude’s nuts.”

And we won’t even talk about Charles Haley and his issues.

Mentality creates a motor, and a motor determines how the athlete performs (reaching total athleticism). I believe that without a boarder line intervention type of mindset, a player can’t tap into the full potential of their ability when it comes to battles in the trenches.

This isn’t the case for all positions. For example, wide receivers and defensive backs are much more precise; they’re calculated with their athleticism. Offensive and defensive trench play is not even in the same realm. Those guys are the biggest players on the field often playing with reckless abandon to achieve their task on every snap.

One of the best defensive line prospects I’ve scouted coming out of college was Florida’s Dominique Easley. When Easley played against the Gators’ rival, Florida State, he used to tell reporters that he wanted them to feel the pain he felt in his heart for 365 days in 60 minutes. When he was healthy, the only word that came to mind to describe how intense Easley was on the field was crazy.

Whether it’s being a perfectionist, being egotistical or having an strange desire for pain and gain, if you’re drafting a pass rusher in the first round, he better be a little crazy. When channeled, crazy can turn into drive at a gear few other players have.

Trevor Sikkema is the Tampa Bay Buccaneers beat reporter and NFL Draft analyst for PewterReport.com. Sikkema, an alumnus of the University of Florida, has covered both college and professional football for much of his career. As a native of the Sunshine State, when he's not buried in social media, Sikkema can be found out and active, attempting to be the best athlete he never was. Sikkema can be reached at: [email protected]